When will India have fusion power plants?

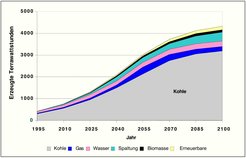

Long-term energy scenario for India / coal predominant / fusion safeguarding the climate

These questions are treated in the recently published study, "Long-term Energy Scenarios for India”, which was conducted by the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) in Ahmedabad, the Max Planck Institute of Plasma Physics (IPP) in Garching, Germany, and the Netherlands Energy Research Foundation (ECN). It forms part of the "Socio-economic Research on Fusion" initiated in the context of the European Fusion Programme.

India’s population - more than one billion already - is increasing annually by some 15 million; the growth rates of the Indian economy are among the highest in the world: from 1975 to 2000 the gross national product trebled, energy consumption - from coal mainly - quadrupled, and demand for electricity quintupled. Indian economists predict a continuation of this rapid pace: in the next hundred years India’s population will increase to 1.6 billion, the gross national product 80-fold, and energy production sevenfold from its present 15 to 110 exajoules.

If the development of India’s energy industry is left to market forces, then in the year 2100 the country’s abundance of coal will provide the bulk of its energy, particularly in the generation of electricity - with fatal consequences for the word-wide efforts to safeguard the climate: over 70 per cent of its electricity will be produced by combustion of coal, five per cent from oil and gas. Seven per cent will be provided by nuclear fission; six per cent will come from renewable energy sources - primarily wind and water power. As a new and capital-intensive technology, fusion cannot compete under these conditions with the other base-load energy suppliers.

Being predominantly based on fossil fuels, this energy production will result in severe environmental pollution. As a reaction to localised air pollution by sulphur and nitrogen oxides by virtue of pressure from the local population, clean technologies will quickly be adopted - and at little expense. Climatically harmful carbon dioxide however, is quite a different matter. By the end of the century emission will increase sevenfold, per capita from the present 0.2 to one tonne of the carbon bound in carbon dioxide. This, admittedly, is still well below the present per capita values in developed countries; the USA already has a per capita emission five times as high. But in view of India’s large population the per capita emission rates add up to 1,700 million tonnes of carbon - a disaster for world-wide climate protection. Since, however, the increasing carbon dioxide emission causes damage "only” globally, but not locally, there will probably be no protest from the population, says Prof. P. R. Shukla of IIM: "India will first solve its own problems, not those of the whole world”.

The forecast would be different if impairment of the climate were to be obviated by limiting the emission of greenhouse gases - e.g. by a tax on carbon dioxide that would make coal combustion more expensive. In order to replace coal-fired power plants, emission-free technologies such as renewable sources and fusion would gain ground. Depending on the carbon dioxide limit, fusion could provide up to ten per cent of the energy in the second half of the century. Fusion power plants with a total output of up to 70 gigawatts would then supply the grid. The approx. 400 terrawatt-hours of electricity would then be almost equivalent to Germany’s present total electricity production.

The computation methods used for the stated long-term study model India’s future economic development and its concomitant energy requirements. Information on the development of energy resources, various energy technologies, and other factors affecting the energy market are derived from separate studies. The model than picks out - under the particular given boundary conditions, such as free rein to the market or limitation of carbon dioxide - the combination of energy technologies incurring the lowest total cost for the system. "As we are looking far into the future 100 years from now, the individual results should not be weighed too finely”, states Dr. Thomas Hamacher of IPP, coordinator of the study. "They do make it obvious, however, that there are no quick solutions to the carbon dioxide problem - it will be with us for a long time”.

Isabella Milch